Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Havana

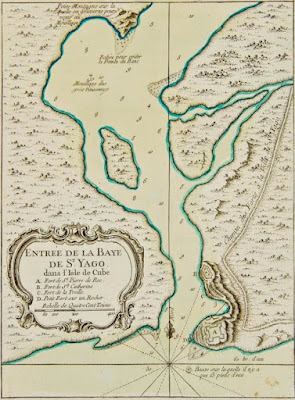

Havana is the capital city, major port, and leading commercial centre of Cuba. The city is one of the 14 Cuban provinces. The city/province has 2.4 million inhabitants, and the urban area over 3.7 million, making Havana the largest city in both Cuba and the Caribbean region. The city extends mostly westward and southward from the bay, which is entered through a narrow inlet and which divides into three main harbours: Marimelena, Guanabacoa, and Atarés. The sluggish Almendares River traverses the city from south to north, entering the Straits of Florida a few miles west of the bay. In 1959 the city halted its growth, and since then has suffered a net loss of living units, despite its population increase.

King Philip II of Spain granted Havana the title of City in 1592 and a royal decree in 1634 recognized its importance by officially designated as the "Key to the New World and Rampart of the West Indies". Havana's coat of arms carries this inscription. The Spaniards began building fortifications, and in 1553 they transferred the governor's residence to Havana from Santiago de Cuba on the eastern end of the island, thus making Havana the de facto capital. The importance of harbour fortifications was early recognized as English, French, and Dutch sea marauders attacked the city in the 16th century. The sinking of the U.S. battleship Maine in Havana's harbor in 1898 was the immediate cause of the Spanish-American War.

Present day Havana is the center of the Cuban government, and various ministries and headquarters of businesses are based there.

The city extends mostly westward and southward from the bay, which is entered through a narrow inlet and which divides into three main harbours: Marimelena, Guanabacoa, and Atarés. The sluggish Almendares River traverses the city from south to north, entering the Straits of Florida a few miles west of the bay. The low hills on which the city lies rise gently from the deep blue waters of the straits. A noteworthy elevation is the 200-foot- (60-metre-) high limestone ridge that slopes up from the east and culminates in the heights of La Cabaña and El Morro, the sites of colonial fortifications overlooking the bay. Another notable rise is the hill to the west that is occupied by the University of Havana and the Prince's Castle.

Havana, like much of Cuba, enjoys a pleasant year-round tropical climate that is tempered by the island's position in the belt of the trade winds and by the warm offshore currents. Average temperatures range from 72 °F (22 °C) in January and February to 82 °F (28 °C) in August. The temperature seldom drops below 50 °F (10 °C). The lowest temperature was 33 °F (1 °C) in Santiago de Las Vegas, Boyeros. The lowest recorded temperature in Cuba was 32 °F (0 °C) in Bainoa, Havana province. Rainfall is heaviest in June and October and lightest from December through April, averaging 46 inches (1.2 m)illimetres) annually. Hurricanes occasionally strike the island, but they ordinarily hit the south coast, and damage in Havana is normally less than elsewhere in the country.

On the night of July 8-9, 2005, the eastern suburbs of the city took a direct hit from Hurricane Dennis, with 100 mph (160 km/h) winds. The storm whipped fierce 10-foot (3.0 m) waves over Havana's seawall, and its winds tore apart pieces of some of the city's crumbling colonial buildings. Chunks of concrete fell from the city's colonial buildings. At least 5,000 homes were damaged in Havana's surrounding province. Three months later, in October 2005, the coastal regions suffered severe flooding following Hurricane Wilma. The table below lists temperature averages throughout the year:

The current Havana area and its natural bay were first visited by Europeans during Sebastián de Ocampo's circumnavigation of the island in 1509. Shortly thereafter, in 1510, the first Spanish colonists arrived from Hispaniola and began the conquest of Cuba.

Conquistador Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar founded Havana on August 25, 1515 on the southern coast of the island, near the present town of Surgidero de Batabanó. Between 1514 and 1519, the city had at least two different establishments. All attempts to found a city on Cuba's south coast failed. The city's location was adjacent to a superb harbor at the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico, and with easy access to the Gulf Stream, the main ocean current that navigators followed when traveling from the Americas to Europe. This location led to Havana’s early development as the principal port of Spain's New World colonies. An early map of Cuba drawn in 1514 places the town at the mouth of the river Onicaxinal, also on the south coast of Cuba. Another establishment was La Chorrera, today in the neighborhood of Puentes Grandes, next to the Almendares River.

The final establishment, commemorated by El Templete, was the sixth town founded by the Spanish on the island, called San Cristobal de la Habana by Pánfilo de Narváez: the name combines San Cristóbal, patron saint of Havana, and Habana, of obscure origin, possibly derived from Habaguanex, a native American chief who controlled that area, as mentioned by Diego Velasquez in his report to the king of Spain. A legend relates that Habana was the name of Habaguanex's beautiful daughter, but no known historical source corroborates this version.

Havana moved to its current location next to what was then called Puerto de Carenas , in 1519. The quality of this natural bay, which now hosts Havana's harbor, warranted this change of location. Bartolomé de las Casas wrote:

...one of the ships, or both, had the need of careening, which is to renew or mend the parts that travel under the water, and to put tar and wax in them, and entered the port we now call Havana, and there they careened so the port was called de Carenas. This bay is very good and can host many ships, which I visited few years after the Discovery... few are in Spain, or elsewhere in the world, that are their equal...

Shortly after the founding of Cuba's first cities, the island served as little more than a base for the Conquista of other lands. Hernán Cortés organized his expedition to Mexico from the island. Cuba, during the first years of the Discovery, provided no immediate wealth to the conquistadores, as it was poor in gold, silver and precious stones, and many of its settlers moved to the more promising lands of Mexico and South America that were being discovered and colonized at the time. The legends of Eldorado and the Seven Cities of Gold attracted many adventurers from Spain, and also from the adjacent colonies, leaving Havana and the rest of Cuba largely unpopulated.

Havana was originally a trading port, and suffered regular attacks by buccaneers, pirates, and French corsairs. The first attack and resultant burning of the city was by the French corsair Jacques de Sores in 1555. The pirate took Havana easily, plundering the city and burning much of it to the ground. De Sores left without obtaining the enormous wealth he was hoping to find in Havana. Such attacks convinced the Spanish Crown to fund the construction of the first fortresses in the main cities — not only to counteract the pirates and corsairs, but also to exert more control over commerce with the West Indies, and to limit the extensive contrabando that had arisen due to the trade restrictions imposed by the Casa de Contratación of Seville .

To counteract pirate attacks on galleon convoys headed for Spain while loaded with New World treasures, the Spanish crown decided to protect its ships by concentrating them in one large fleet, which would traverse the Atlantic Ocean as a group. A single merchant fleet could more easily be protected by the Spanish Armada. Following a royal decree in 1561, all ships headed for Spain were required to assemble this fleet in the Havana Bay. Ships arrived from May through August, waiting for the best weather conditions, and together, the fleet departed Havana for Spain by September.

This naturally boosted commerce and development of the adjacent city of Havana . Goods traded in Havana included gold, silver, alpaca wool from the Andes, emeralds from Colombia, mahoganies from Cuba and Guatemala, leather from the Guajira, spices, sticks of dye from Campeche, corn, manioc, and cocoa. Ships from all over the New World carried products first to Havana, in order to be taken by the fleet to Spain. The thousands of ships gathered in the city's bay also fueled Havana's agriculture and manufacture, since they had to be supplied with food, water, and other products needed to traverse the ocean. In 1563, the Capitán General (the Spanish Governor of the island) moved his residence from Santiago de Cuba to Havana, by reason of that city's newly gained wealth and importance, thus unofficially sanctioning its status as capital of the island.

On December 20, 1592, King Philip II of Spain granted Havana the title of City. Later on, the city would be officially designated as "Key to the New World and Rampart of the West Indies" by the Spanish crown. In the meantime, efforts to build or improve the defensive infrastructures of the city continued. The San Salvador de la Punta castle guarded the west entrance of the bay, while the Castillo de los Tres Reyes Magos del Morro guarded the eastern entrance. The Castillo de la Real Fuerza defended the city's center, and doubled as the Governor's residence until a more comfortable palace was built. Two other defensive towers, La Chorrera and San Lázaro were also built in this period.

Havana expanded greatly in the 17th century. New buildings were constructed from the most abundant materials of the island, mainly wood, combining various Iberian architectural styles, as well as borrowing profusely from Canarian characteristics. During this period the city also built civic monuments and religious constructions. The convent of St Augustin, El Morro Castle, the chapel of the Humilladero, the fountain of Dorotea de la Luna in La Chorrera, the church of the Holy Angel, the hospital of San Lazaro, the monastery of Santa Teresa and the convent of San Felipe Neri were all completed in this era.

In 1649 a fatal epidemic brought from Cartagena in Colombia, affected a third of the population of Havana. On November 30, 1665, Queen Mariana of Austria, widow of King Philip IV of Spain, ratified the heraldic shield of Cuba, which took as its symbolic motifs the first three castles of Havana: the Real Fuerza, the Tres Santos Reyes Magos del Morro and San Salvador de la Punta. The shield also displayed a symbolic golden key to represent the title "Key to the Gulf". On 1674, the works for the City Walls were started, as part of the fortification efforts. They would be completed by 1740.

By the middle of the 18th century Havana had more than seventy thousand inhabitants, and was the third largest city in the Americas, ranking behind Lima and Mexico City but ahead of Boston and New York.

The city was captured by the British during the Seven Years' War. The episode began on June 6, 1762, when at dawn, a British fleet, comprising more than 50 ships and a combined force of over 11,000 men of the Royal Navy and Army, sailed into Cuban waters and made an amphibious landing east of Havana. The invaders seized the heights known as La Cabaña on the east side of the harbor and commenced a bombardment of nearby El Morro Castle, as well as the city itself. After a two month siege, El Morro was attacked and taken on 30 July 1762. The city formally surrendered on 13 August. It was subsequently governed by Sir George Keppel on behalf of Great Britain. Although the British only lost 560 men to combat injuries during the siege, more than half their forces ultimately died due to illness, yellow fever in particular.

The British immediately opened up trade with their North American and Caribbean colonies, causing a rapid transformation of Cuban society. Food, horses and other goods flooded into the city, and thousands of slaves from West Africa were transported to the island to work on the undermanned sugar plantations. Though Havana, which had become the third largest city in the new world, was to enter an era of sustained development and strengthening ties with North America, the British occupation was not to last. Pressure from London by sugar merchants fearing a decline in sugar prices forced a series of negotiations with the Spanish over colonial territories. Less than a year after Havana was seized, the Peace of Paris was signed by the three warring powers thus ending the Seven Years' War. The treaty gave Britain Florida in exchange for Cuba on the recommendation of the French, who advised that declining the offer could result in Spain losing Mexico and much of the South American mainland to the British.

After regaining the city, the Spanish transformed Havana into the most heavily fortified city in the Americas. Construction began on what was to become the Fortress of San Carlos de la Cabaña, the biggest Spanish fortification in the New World. The work extended for eleven years and was enormously costly, but on completion the fort was considered an unassailable bastion and essential to Havana's defence. It was provided with a large number of cannons forged in Barcelona. Other fortifications were constructed, as well: the castle of Atarés defended the Shipyard in the inner bay, while the castle of El Príncipe guarded the city from the west. Several cannon batteries located along the bay's canal ensured that no place in the harbor remained undefended.

The Havana cathedral was constructed in 1748 as a Jesuit church, and converted in 1777 into the Parroquial Mayor church, after the Suppression of the Jesuits in Spanish territory in 1767. In 1788, it formally became a Cathedral. Between 1789 and 1790 Cuba was apportioned into an individual diocese by the Roman Catholic Church. On January 15, 1796, the remains of Christopher Columbus were transported to the island from Santo Domingo. They rested here until 1898, when they were transferred to Seville's Cathedral, after Spain's loss of Cuba.

Havana's shipyard was extremely active, thanks to the lumber resources available in the vicinity of the city. The Santísima Trinidad was the largest warship of her time. Launched in 1769, she was about 62 meters long, had three decks and 120 cannons. She was later upgraded to as many as 144 cannons and four decks. She sank following the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. This ship cost 40.000 pesos fuertes of the time, which gives an idea of the importance of the Arsenal, by comparing its cost to the 26 million pesos fuertes and 109 ships produced during the Arsenal's existence.

As trade between Caribbean and North American states increased in the early 19th century, Havana became a flourishing and fashionable city. Havana's theaters featured the most distinguished actors of the age, and prosperity amongst the burgeoning middle-class led to expensive new classical mansions being erected. During this period Havana became known as the Paris of the Antilles.

The 19th century opened with the arrival in Havana of Alexander von Humboldt, who was impressed by the vitality of the port. In 1837, the first railroad was constructed, a 51 km stretch between Havana and Bejucal, which was used for transporting sugar from the valley of Guinness to the harbor. With this, Cuba became the fifth country in the world to have a railroad, and the first Spanish-speaking country. Throughout the century, Havana was enriched by the construction of additional cultural facilities, such as the Tacon Teatre, one of the most luxurious in the world, the Artistic and Literary Liceo and the theater Coliseo.

In 1863, the city walls were knocked down so that the metropolis could be enlarged. At the end of the century, the well-off classes moved to the quarter of Vedado. Later, they emigrated towards Miramar, and today, evermore to the west, they have settled in Siboney. At the end of the 19th century, Havana witnessed the final moments of Spanish colonialism in America, which ended definitively when the United States warship Maine was sunk in its port, giving that country the pretext to invade the island. The 20th century began with Havana, and therefore Cuba, under occupation by the USA. In 1906 the Bank of Nova Scotia opened the first branch in Havana. By 1931 it had three branches in Havana.

King Philip II of Spain granted Havana the title of City in 1592 and a royal decree in 1634 recognized its importance by officially designated as the "Key to the New World and Rampart of the West Indies". Havana's coat of arms carries this inscription. The Spaniards began building fortifications, and in 1553 they transferred the governor's residence to Havana from Santiago de Cuba on the eastern end of the island, thus making Havana the de facto capital. The importance of harbour fortifications was early recognized as English, French, and Dutch sea marauders attacked the city in the 16th century. The sinking of the U.S. battleship Maine in Havana's harbor in 1898 was the immediate cause of the Spanish-American War.

Present day Havana is the center of the Cuban government, and various ministries and headquarters of businesses are based there.

The city extends mostly westward and southward from the bay, which is entered through a narrow inlet and which divides into three main harbours: Marimelena, Guanabacoa, and Atarés. The sluggish Almendares River traverses the city from south to north, entering the Straits of Florida a few miles west of the bay. The low hills on which the city lies rise gently from the deep blue waters of the straits. A noteworthy elevation is the 200-foot- (60-metre-) high limestone ridge that slopes up from the east and culminates in the heights of La Cabaña and El Morro, the sites of colonial fortifications overlooking the bay. Another notable rise is the hill to the west that is occupied by the University of Havana and the Prince's Castle.

Havana, like much of Cuba, enjoys a pleasant year-round tropical climate that is tempered by the island's position in the belt of the trade winds and by the warm offshore currents. Average temperatures range from 72 °F (22 °C) in January and February to 82 °F (28 °C) in August. The temperature seldom drops below 50 °F (10 °C). The lowest temperature was 33 °F (1 °C) in Santiago de Las Vegas, Boyeros. The lowest recorded temperature in Cuba was 32 °F (0 °C) in Bainoa, Havana province. Rainfall is heaviest in June and October and lightest from December through April, averaging 46 inches (1.2 m)illimetres) annually. Hurricanes occasionally strike the island, but they ordinarily hit the south coast, and damage in Havana is normally less than elsewhere in the country.

On the night of July 8-9, 2005, the eastern suburbs of the city took a direct hit from Hurricane Dennis, with 100 mph (160 km/h) winds. The storm whipped fierce 10-foot (3.0 m) waves over Havana's seawall, and its winds tore apart pieces of some of the city's crumbling colonial buildings. Chunks of concrete fell from the city's colonial buildings. At least 5,000 homes were damaged in Havana's surrounding province. Three months later, in October 2005, the coastal regions suffered severe flooding following Hurricane Wilma. The table below lists temperature averages throughout the year:

The current Havana area and its natural bay were first visited by Europeans during Sebastián de Ocampo's circumnavigation of the island in 1509. Shortly thereafter, in 1510, the first Spanish colonists arrived from Hispaniola and began the conquest of Cuba.

Conquistador Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar founded Havana on August 25, 1515 on the southern coast of the island, near the present town of Surgidero de Batabanó. Between 1514 and 1519, the city had at least two different establishments. All attempts to found a city on Cuba's south coast failed. The city's location was adjacent to a superb harbor at the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico, and with easy access to the Gulf Stream, the main ocean current that navigators followed when traveling from the Americas to Europe. This location led to Havana’s early development as the principal port of Spain's New World colonies. An early map of Cuba drawn in 1514 places the town at the mouth of the river Onicaxinal, also on the south coast of Cuba. Another establishment was La Chorrera, today in the neighborhood of Puentes Grandes, next to the Almendares River.

The final establishment, commemorated by El Templete, was the sixth town founded by the Spanish on the island, called San Cristobal de la Habana by Pánfilo de Narváez: the name combines San Cristóbal, patron saint of Havana, and Habana, of obscure origin, possibly derived from Habaguanex, a native American chief who controlled that area, as mentioned by Diego Velasquez in his report to the king of Spain. A legend relates that Habana was the name of Habaguanex's beautiful daughter, but no known historical source corroborates this version.

Havana moved to its current location next to what was then called Puerto de Carenas , in 1519. The quality of this natural bay, which now hosts Havana's harbor, warranted this change of location. Bartolomé de las Casas wrote:

...one of the ships, or both, had the need of careening, which is to renew or mend the parts that travel under the water, and to put tar and wax in them, and entered the port we now call Havana, and there they careened so the port was called de Carenas. This bay is very good and can host many ships, which I visited few years after the Discovery... few are in Spain, or elsewhere in the world, that are their equal...

Shortly after the founding of Cuba's first cities, the island served as little more than a base for the Conquista of other lands. Hernán Cortés organized his expedition to Mexico from the island. Cuba, during the first years of the Discovery, provided no immediate wealth to the conquistadores, as it was poor in gold, silver and precious stones, and many of its settlers moved to the more promising lands of Mexico and South America that were being discovered and colonized at the time. The legends of Eldorado and the Seven Cities of Gold attracted many adventurers from Spain, and also from the adjacent colonies, leaving Havana and the rest of Cuba largely unpopulated.

Havana was originally a trading port, and suffered regular attacks by buccaneers, pirates, and French corsairs. The first attack and resultant burning of the city was by the French corsair Jacques de Sores in 1555. The pirate took Havana easily, plundering the city and burning much of it to the ground. De Sores left without obtaining the enormous wealth he was hoping to find in Havana. Such attacks convinced the Spanish Crown to fund the construction of the first fortresses in the main cities — not only to counteract the pirates and corsairs, but also to exert more control over commerce with the West Indies, and to limit the extensive contrabando that had arisen due to the trade restrictions imposed by the Casa de Contratación of Seville .

To counteract pirate attacks on galleon convoys headed for Spain while loaded with New World treasures, the Spanish crown decided to protect its ships by concentrating them in one large fleet, which would traverse the Atlantic Ocean as a group. A single merchant fleet could more easily be protected by the Spanish Armada. Following a royal decree in 1561, all ships headed for Spain were required to assemble this fleet in the Havana Bay. Ships arrived from May through August, waiting for the best weather conditions, and together, the fleet departed Havana for Spain by September.

This naturally boosted commerce and development of the adjacent city of Havana . Goods traded in Havana included gold, silver, alpaca wool from the Andes, emeralds from Colombia, mahoganies from Cuba and Guatemala, leather from the Guajira, spices, sticks of dye from Campeche, corn, manioc, and cocoa. Ships from all over the New World carried products first to Havana, in order to be taken by the fleet to Spain. The thousands of ships gathered in the city's bay also fueled Havana's agriculture and manufacture, since they had to be supplied with food, water, and other products needed to traverse the ocean. In 1563, the Capitán General (the Spanish Governor of the island) moved his residence from Santiago de Cuba to Havana, by reason of that city's newly gained wealth and importance, thus unofficially sanctioning its status as capital of the island.

On December 20, 1592, King Philip II of Spain granted Havana the title of City. Later on, the city would be officially designated as "Key to the New World and Rampart of the West Indies" by the Spanish crown. In the meantime, efforts to build or improve the defensive infrastructures of the city continued. The San Salvador de la Punta castle guarded the west entrance of the bay, while the Castillo de los Tres Reyes Magos del Morro guarded the eastern entrance. The Castillo de la Real Fuerza defended the city's center, and doubled as the Governor's residence until a more comfortable palace was built. Two other defensive towers, La Chorrera and San Lázaro were also built in this period.

Havana expanded greatly in the 17th century. New buildings were constructed from the most abundant materials of the island, mainly wood, combining various Iberian architectural styles, as well as borrowing profusely from Canarian characteristics. During this period the city also built civic monuments and religious constructions. The convent of St Augustin, El Morro Castle, the chapel of the Humilladero, the fountain of Dorotea de la Luna in La Chorrera, the church of the Holy Angel, the hospital of San Lazaro, the monastery of Santa Teresa and the convent of San Felipe Neri were all completed in this era.

In 1649 a fatal epidemic brought from Cartagena in Colombia, affected a third of the population of Havana. On November 30, 1665, Queen Mariana of Austria, widow of King Philip IV of Spain, ratified the heraldic shield of Cuba, which took as its symbolic motifs the first three castles of Havana: the Real Fuerza, the Tres Santos Reyes Magos del Morro and San Salvador de la Punta. The shield also displayed a symbolic golden key to represent the title "Key to the Gulf". On 1674, the works for the City Walls were started, as part of the fortification efforts. They would be completed by 1740.

By the middle of the 18th century Havana had more than seventy thousand inhabitants, and was the third largest city in the Americas, ranking behind Lima and Mexico City but ahead of Boston and New York.

The city was captured by the British during the Seven Years' War. The episode began on June 6, 1762, when at dawn, a British fleet, comprising more than 50 ships and a combined force of over 11,000 men of the Royal Navy and Army, sailed into Cuban waters and made an amphibious landing east of Havana. The invaders seized the heights known as La Cabaña on the east side of the harbor and commenced a bombardment of nearby El Morro Castle, as well as the city itself. After a two month siege, El Morro was attacked and taken on 30 July 1762. The city formally surrendered on 13 August. It was subsequently governed by Sir George Keppel on behalf of Great Britain. Although the British only lost 560 men to combat injuries during the siege, more than half their forces ultimately died due to illness, yellow fever in particular.

The British immediately opened up trade with their North American and Caribbean colonies, causing a rapid transformation of Cuban society. Food, horses and other goods flooded into the city, and thousands of slaves from West Africa were transported to the island to work on the undermanned sugar plantations. Though Havana, which had become the third largest city in the new world, was to enter an era of sustained development and strengthening ties with North America, the British occupation was not to last. Pressure from London by sugar merchants fearing a decline in sugar prices forced a series of negotiations with the Spanish over colonial territories. Less than a year after Havana was seized, the Peace of Paris was signed by the three warring powers thus ending the Seven Years' War. The treaty gave Britain Florida in exchange for Cuba on the recommendation of the French, who advised that declining the offer could result in Spain losing Mexico and much of the South American mainland to the British.

After regaining the city, the Spanish transformed Havana into the most heavily fortified city in the Americas. Construction began on what was to become the Fortress of San Carlos de la Cabaña, the biggest Spanish fortification in the New World. The work extended for eleven years and was enormously costly, but on completion the fort was considered an unassailable bastion and essential to Havana's defence. It was provided with a large number of cannons forged in Barcelona. Other fortifications were constructed, as well: the castle of Atarés defended the Shipyard in the inner bay, while the castle of El Príncipe guarded the city from the west. Several cannon batteries located along the bay's canal ensured that no place in the harbor remained undefended.

The Havana cathedral was constructed in 1748 as a Jesuit church, and converted in 1777 into the Parroquial Mayor church, after the Suppression of the Jesuits in Spanish territory in 1767. In 1788, it formally became a Cathedral. Between 1789 and 1790 Cuba was apportioned into an individual diocese by the Roman Catholic Church. On January 15, 1796, the remains of Christopher Columbus were transported to the island from Santo Domingo. They rested here until 1898, when they were transferred to Seville's Cathedral, after Spain's loss of Cuba.

Havana's shipyard was extremely active, thanks to the lumber resources available in the vicinity of the city. The Santísima Trinidad was the largest warship of her time. Launched in 1769, she was about 62 meters long, had three decks and 120 cannons. She was later upgraded to as many as 144 cannons and four decks. She sank following the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. This ship cost 40.000 pesos fuertes of the time, which gives an idea of the importance of the Arsenal, by comparing its cost to the 26 million pesos fuertes and 109 ships produced during the Arsenal's existence.

As trade between Caribbean and North American states increased in the early 19th century, Havana became a flourishing and fashionable city. Havana's theaters featured the most distinguished actors of the age, and prosperity amongst the burgeoning middle-class led to expensive new classical mansions being erected. During this period Havana became known as the Paris of the Antilles.

The 19th century opened with the arrival in Havana of Alexander von Humboldt, who was impressed by the vitality of the port. In 1837, the first railroad was constructed, a 51 km stretch between Havana and Bejucal, which was used for transporting sugar from the valley of Guinness to the harbor. With this, Cuba became the fifth country in the world to have a railroad, and the first Spanish-speaking country. Throughout the century, Havana was enriched by the construction of additional cultural facilities, such as the Tacon Teatre, one of the most luxurious in the world, the Artistic and Literary Liceo and the theater Coliseo.

In 1863, the city walls were knocked down so that the metropolis could be enlarged. At the end of the century, the well-off classes moved to the quarter of Vedado. Later, they emigrated towards Miramar, and today, evermore to the west, they have settled in Siboney. At the end of the 19th century, Havana witnessed the final moments of Spanish colonialism in America, which ended definitively when the United States warship Maine was sunk in its port, giving that country the pretext to invade the island. The 20th century began with Havana, and therefore Cuba, under occupation by the USA. In 1906 the Bank of Nova Scotia opened the first branch in Havana. By 1931 it had three branches in Havana.

Cuba

The Republic of Cuba is an island country in the Caribbean. It consists of the island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city.Cuba is home to over 11 million people and is the most populous insular nation in the Caribbean. Its people, culture, and customs draw from diverse sources, including the aboriginal Taíno and Ciboney peoples; the period of Spanish colonialism; the introduction of African slaves; and its proximity to the United States.

Cuba is an archipelago of islands located in the northern Caribbean Sea at the confluence with the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. The United States lies to the north-west, the Bahamas to the north, Haiti to the east, Jamaica and the Cayman Islands to the south, and Mexico to the west. Cuba is the principal island, surrounded by four smaller groups of islands: the Colorados Archipelago on the northwestern coast, the Sabana-Camagüey Archipelago on the north-central Atlantic coast, the Jardines de la Reina on the south-central coast and the Canarreos Archipelago on the southwestern coast. The main island is 766 km (476 mi) long, constituting most of the nation's land area (105,006 km2 (40,543 sq mi)) and is the sixteenth-largest island in the world by land area. The main island consists mostly of flat to rolling plains apart from the Sierra Maestra mountains in the southeast, whose highest point is Pico Turquino (1,975 m (6,480 ft)). The second largest island is Isla de la Juventud (Isle of Youth) in the Canarreos archipelago, with an area of 3,056 km2 (1,180 sq mi). Cuba has a total land area of 110,860 km2 (42,803 sq mi).

The local climate is tropical, though moderated by northeasterly trade winds that blow year-round. In general , there is a drier season from November to April, and a rainier season from May to October. The average temperature is 21 °C (70 °F) in January and 27 °C (81 °F) in July. The warm temperatures of the Caribbean Sea and the fact that Cuba sits across the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico combine to make the country prone to frequent hurricanes. These are most common in September and October.

The most important mineral resource is nickel, of which Cuba has the world's second largest reserves after Russia. A Canadian energy company operates a large nickel mining facility in Moa. Cuba is also the world's fifth largest producer of refined cobalt, a byproduct of nickel mining operations.[91] Recent oil exploration has revealed that the North Cuba Basin could produce approximately 4.6 billion barrels (730,000,000 m3) to 9.3 billion barrels (1.48×109 m3) of oil. In 2006, Cuba started to test-drill these locations for possible exploitation.

Prior to the arrival of the Spanish, the island was inhabited by Native American peoples known as the Taíno and Ciboney whose ancestors migrated from the mainland of North, Central and South America several centuries earlier. The Taíno were farmers and the Ciboney were farmers and hunter-gatherers; some have suggested that copper trade was significant and mainland artifacts have been found.

On October 12, 1492, Christopher Columbus landed near what is now Baracoa, claimed the island for the new Kingdom of Spain, and named Isla Juana after Juan, Prince of Asturias. In 1511 the first Spanish settlement was founded by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar at Baracoa; other towns soon followed including the future capital, San Cristobal de la Habana founded in 1515. The Spanish enslaved the approximately 100,000 indigenous people who resisted conversion to Christianity, setting them primarily to the task of searching for gold, and within a century European infectious diseases had virtually wiped out the indigenous people.

Cuba remained a Spanish possession for almost 400 years (1511–1898), with an economy based on plantations agriculture, mining and the export of sugar, coffee and tobacco to Europe and later to North America. The work was done primarily by African slaves brought to the island when the British owned it in 1762. The small land-owning elite of Spanish settlers held social and economic power, supported by a population of Spaniards born on the island , other Europeans, and African-descended slaves. In the 1820s, when the rest of Spain's empire in Latin America rebelled and formed independent states, Cuba remained loyal, although there was some agitation for independence, leading the Spanish Crown to give it the motto "La Siempre Fidelísima Isla" . This loyalty was due partly to Cuban settlers' dependence on Spain for trade, protection from pirates, protection against a slave rebellion and partly because they feared the rising power of the United States more than they disliked Spanish rule.

Independence from Spain was the motive for a rebellion in 1868 led by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, resulting in a prolonged conflict known as the Ten Years' War. The U.S. declined to recognize the new Cuban government, though many European and Latin American nations had done so. In 1878 the Pact of Zanjón ended the conflict, with Spain promising greater autonomy to Cuba. In 1879–1880, Cuban patriot Calixto Garcia attempted to start another war, known as the Little War, but received little support. Slavery was abolished in 1886, although the African-descended minority remained socially and economically oppressed. During this period, rural poverty in Spain provoked by the Spanish Revolution of 1868 and its aftermath led to increased Spanish emigration to Cuba. During the 1890s pro-independence agitation was revived in part by resentment of the restrictions imposed on Cuban trade by Spain and hostility to Spain's increasingly oppressive and incompetent administration of Cuba. Few of Spain's promises for economic reform in the Pact of Zanjón were kept.

In 1892, an exiled dissident, José Martí, founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party in New York, with the aim of achieving Cuban independence. In January 1895, Martí travelled to Montecristi, Santo Domingo to join the efforts of Máximo Gómez. Martí wrote down his political views in the Manifesto of Montecristi. Fighting against the Spanish army began in Cuba on 24 February 1895, but Marti was unable to reach Cuba until 11 April 1895. Marti was killed on 19 May 1895, in the battle of Dos Rios. His death immortalized him and he has become Cuba's national hero. Around 200,000 Spanish troops outnumbered the much smaller rebel army which relied mostly on guerrilla and sabotage tactics. The Spaniards began a campaign of suppression. General Valeriano Weyler, military governor of Cuba, herded the rural population into what he called reconcentrados, described by international observers as "fortified towns". These are often considered the prototype for 20th century concentration camps. Between 200,000 and 400,000 Cuban civilians died from starvation and disease in the camps, numbers verified by the Red Cross and U.S. Senator Redfield Proctor. U.S. and European protests against Spanish conduct on the island followed.

The U.S. battleship Maine arrived in Havana on 25 January 1898 to offer protection to the 8,000 American residents on the island; but the Spanish saw this as intimidation. On the evening of 15 February 1898, the Maine blew up in the harbor, killing 252 crew that night; another 8 died of their wounds in hospital over the next few days. A Naval Board of Inquiry, headed by Captain William Sampson, was appointed to investigate the cause of the explosion on the Maine. Having examined the wreck and taken testimony from eyewitnesses and experts, the board reported on 21 March 1898, that the Maine had been destroyed by "a double magazine set off from the exterior of the ship, which could only have been produced by a mine". The facts remain disputed today, although an investigation by Admiral Hyman G. Rickover in 1976 established that the blast was most likely a large internal explosion, caused by spontaneous combustion in inadequately ventilated bituminous coal which ignited gunpowder in an adjacent magazine. The board was unable to fix the responsibility for the disaster, but a furious American populace, fueled by an active press—notably the newspapers of William Randolph Hearst—concluded that the Spanish were to blame amd demanded action. The U.S. Congress passed a resolution calling for intervention and President William McKinley complied. Spain and the United States declared war on each other in late April.

After the Spanish-American War, Spain and the United States signed the Treaty of Paris (1898), by which Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam were ceded to the U.S. for the sum of $20 million. Under the same treaty Spain relinquished all claim of sovereignty over the title to Cuba. Theodore Roosevelt, who had fought in the Spanish-American War and had some sympathies with the independence movement, succeeded McKinley as U.S. President in 1901 and abandoned the 20-year treaty proposal. Instead, Cuba gained formal independence from the United States on May 20, 1902 as the Republic of Cuba. Under the new constitution, however, the U.S. retained the right to intervene in Cuban affairs and to supervise its finances and foreign relations. Under the Platt Amendment, the U.S. leased the Guantánamo Bay naval base from Cuba.

In 1906, following disputed elections, the first president, Tomás Estrada Palma, faced an armed revolt by independence war veterans who defeated the meager government forces. The U.S. intervened by occupying Cuba and named Charles Edward Magoon as Governor for three years. For many years afterwards, Cuban historians attributed Magoon's governorship as having introduced political and social corruption. In 1908 self-government was restored when José Miguel Gómez was elected President, but the U.S. continued intervening in Cuban affairs. In 1912 the Partido Independiente de Color attempted to establish a separate black republic in Oriente Province, but were suppressed by General Monteagudo with considerable bloodshed.

During World War I, Cuba shipped considerable quantities of sugar to Britain, avoiding U-boat attack, by the subterfuge of shipping sugar to Sweden. The Menocal government declared war on Germany very soon after the U.S. did.

Despite frequent outbreaks of disorder, constitutional government was maintained until 1930, when Gerardo Machado y Morales suspended the constitution. During Machado's tenure, a nationalistic economic program was pursued with several major national development projects undertaken, including Carretera Central and El Capitolio. Machado's hold on power was weakened following a decline in demand for exported agricultural produce due to the Great Depression, and to attacks first by independence war veterans, and later by covert terrorist organizations, principally the ABC.

During a general strike in which the Communist Party took the side of Machado the senior elements of the Cuban army forced Machado into exile and installed Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y Quesada, son of Cuba's founding father , as President. During September 4–5, 1933 a second coup overthrew Céspedes, leading to the formation of the first Ramón Grau government. Notable events in this violent period include the separate sieges of Hotel Nacional de Cuba and Atares Castle. This government lasted 100 days but engineered radical socialistic changes in Cuban society and a rejection of the Platt amendment. In 1934 Fulgencio Batista and the army replaced Grau with Carlos Mendieta.

Batista was finally elected as President democratically in the elections of 1940,[ and his administration carried out major social reforms. Several members of the Communist Party held office under his administration. Batista's administration formally took Cuba to the Allies of World War II camp in the World War II, declaring war on Japan on December 9, 1941, then on Germany and Italy on December 11, 1941. Cuba was not greatly involved in combat during World War II.

Ramón Grau won the 1944 elections. Carlos Prío Socarrás won the 1948 elections. The influx of investment fueled a boom which did much to raise living standards across the board and create a prosperous middle class in most urban areas, although the gap between rich and poor became wider and more obvious.

The 1952 election was a three-way race. Roberto Agramonte of the Ortodoxos party led in all the polls, followed by Dr Aurelio Hevia of the Auténtico party, and running a distant third was Batista, seeking a return to office. Both Agramonte and Hevia had decided to name Col. Ramón Barquín to head the Cuban armed forces after the elections. Barquín, then a diplomat in Washington, DC, was a top officer who commanded the respect of the professional army and had promised to eliminate corruption in the ranks. Batista feared that Barquín would oust him and his followers, and when it became apparent that Batista had little chance of winning, he staged a coup on March 10, 1952 and held power with the backing of a nationalist section of the army as a "provisional president" for the next two years. Justo Carrillo told Barquín in Washington in March 1952 that the inner circles knew that Batista had aimed the coup at him; they immediately began to conspire to oust Batista and restore democracy and civilian government in what was later dubbed La Conspiracion de los Puros de 1956 . In 1954 Batista agreed to elections. The Partido Auténtico put forward ex-President Grau as their candidate, but he withdrew amid allegations that Batista was rigging the elections in advance.

In April 1956 Batista had given the orders for Barquín to become General and chief of the army. But Barquin decided to move forward with his coup and secure total power. On April 4, 1956 a coup by hundreds of career officers led by Col. Barquín was frustrated by Rios Morejon. The coup broke the backbone of the Cuban armed forces. The officers were sentenced to the maximum terms allowed by Cuban Martial Law. Barquín was sentenced to solitary confinement for eight years. La Conspiración de los Puros resulted in the imprisonment of the commanders of the armed forces and the closing of the military academies.

Cuba had Latin America's highest per capita consumption rates of meat, vegetables, cereals, automobiles, telephones and radios. In 1958, Cuba was a relatively well-advanced country, certainly by Latin American standards, and in some cases by world standards.Cuban's workers enjoyed some of the highest wages in the world. Cuba attracted more immigrants, primarily from Europe, as a percentage of population than the US. The United Nations noted Cuba for its large middle class. On the other hand, Cuba was affected by perhaps the largest labor union privileges in Latin America, including bans on dismissals and mechanization. They were obtained in large measure "at the cost of the unemployed and the peasants", leading to disparities. Between 1933 and 1958, Cuba extended economic regulations enormously, causing economic problems. Unemployment became relatively large; graduates entering the workforce could not find jobs. The middle class, which compared Cuba to the United States, became increasingly dissatisfied with the unemployment, while labor unions supported Batista until the very end.

The United States government imposed an arms embargo on the Cuban government on March 14, 1958. On December 2, 1956 a party of 82 people, led by Fidel Castro, had landed with the intention of establishing an armed resistance movement in the Sierra Maestra. By late 1958 they had broken out of the Sierra Maestra and launched a general insurrection, joined by various people. When the group captured Santa Clara, Batista fled the country to exile in Portugal. Barquín negotiated the symbolic change of command between Camilo Cienfuegos, Che Guevara, Raul Castro and his brother Fidel Castro, after the Supreme Court decided that the Revolution was the source of law and its representative should assume command. Castro's forces entered the capital on January 8, 1959. Shortly afterwards, a liberal lawyer, Dr Manuel Urrutia Lleó became president; he was backed by Castro's 26th of July Movement, because they believed his appointment would be welcomed by the United States. Disagreements within the government culminated in Urrutia's resignation in July 1959; he was replaced by Osvaldo Dorticós, who served as president until 1976. Castro became prime minister in February 1959, succeeding José Miró in that post.

Fidel Castro became prime minister of Cuba in February 1959. In its first year, the new revolutionary government expropriated private property with little or no compensation, nationalised public utilities, tightened controls on the private sector and closed down the mafia-controlled gambling industry. The CIA conspired with the Chicago mafia in 1960 and 1961 to assassinate Fidel Castro, according to documents declassified in 2007.

Some of these measures were undertaken by Fidel Castro's government in the name of the program outlined in the Manifesto of the Sierra Maestra, while in the Sierra Maestra. The government nationalized private property totaling about $25 billion US dollars, out of which American property made up only over US $1.0 billions.

By the end of 1960, all opposition newspapers had been closed down, and all radio and television stations were in state control. Moderates, teachers and professors were purged. In any year, about 20,000 dissenters were held and tortured under inhuman prison conditions.Groups such as homosexuals were locked up in internment camps in the 1960s, where they were subject to medical-political "re-education". One estimate is that 15,000 to 17,000 people were executed. The Communist Party strengthened its one-party rule, with Castro as supreme leader. Fidel's brother, Raul Castro, became the army chief. Loyalty to Castro became the primary criteria for all appointments. In September 1960, the regime created a system known as Committees for the Defense of the Revolution , which provided neighborhood spying. In the 1961 New Year's Day parade, the administration exhibited Soviet tanks and other weapons.Eventually, the tiny island nation built up the second largest armed forces in Latin America, second only to Brazil. Cuba became a privileged client-state of the Soviet Union.

By 1961, hundreds of thousands of Cubans had left for the United States. The 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion was an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow the Cuban government by a U.S.-trained force of Cuban exiles with U.S. military support. The plan was launched in April 1961, less than three months after John F. Kennedy became the U.S. President. The Cuban armed forces, trained and equipped by Eastern Bloc nations, defeated the exiles in three days. The bad Cuban-American relations were exacerbated the following year by the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the Kennedy administration demanded the immediate withdrawal of Soviet missiles placed in Cuba, which was a response to U.S. nuclear missiles in Turkey and the Middle East. The Soviets and Americans soon agreed on the removal of Soviet missiles from Cuba and American missiles secretly from Turkey and the Middle East within a few months. Kennedy also agreed not to invade Cuba in the future. Cuban exiles captured during the Bay of Pigs Invasion were exchanged for a shipment of supplies from America.[34] By 1963, Cuba was moving towards a full-fledged Communist system modeled on the USSR. The U.S. imposed a complete diplomatic and commercial embargo on Cuba and began Operation Mongoose.

In 1965, Castro merged his revolutionary organizations with the Communist Party, of which he became First Secretary, and Blas Roca became Second Secretary. Roca was succeeded by Raúl Castro, who, as Defense Minister and Fidel's closest confidant, became and has remained the second most powerful figure in Cuba. Raúl's position was strengthened by the departure of Che Guevara to launch unsuccessful insurrectionss in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and then Bolivia, where he was killed in 1967.

During the 1970s, Castro dispatched tens of thousands troops in support of Soviet-supported wars in Africa, particularly the MPLA in Angola and Mengistu Haile Mariam in Ethiopia. The standard of living in 1970s was "extremely spartan" and discontent was rife. Fidel Castro admitted the failures of economic policies in a 1970 speech. By the mid-1970s, Castro started economic reforms.

Cuba was expelled from the Organization of American States in 1962 in support of the U.S. embargo, but in 1975 the OAS lifted all sanctions against Cuba and both Mexico and Canada broke ranks with the US by developing closer relations with Cuba. On 3 June 2009 the OAS adopted a contentious resolution to end the 47-year exclusion of Cuba, but the U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton walked out in protest as the resolution was being drafted. Cuban leaders have repeatedly announced they are not interested in rejoining the OAS.

As of 2002, some 1.2 million persons of Cuban background (about 10% of the current population of Cuba) reside in the U.S., Many of them left the island for the U.S., often by sea in small boats and fragile rafts. On 6 April 1980, 10,000 Cubans stormed the Peruvian embassy in Havana seeking political asylum. The following day, the Cuban government granted permission for the emigration of Cubans seeking refuge in the Peruvian embassy. On 16 April, 500 Cubans left the Peruvian Embassy for Costa Rica. On 21 April, many of those Cubans started arriving in Miami via private boats and were halted by the U.S. State Department, but the emigration continued, because Castro allowed anyone who desired to leave the country to do so through the port of Mariel. Over 125,000 Cubans emigrated to the U.S. before the flow of vessels ended on 15 June.

Castro's rule was severely tested in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse . The food shortages were similar to North Korea; priority was given to the elite classes and the military, while ordinary people had little to eat. The regime did not accept American donations of food, medicines and cash until 1993. On 5 August 1994, state security dispersed protesters in a spontaneous popular uprising in Havana.

Cuba has found a new source of aid and support in the People's Republic of China, and new allies in Hugo Chávez, President of Venezuela and Evo Morales, President of Bolivia, both major oil and gas exporters. In 2003, the regime arrested and imprisoned a large number of civil activists, a period known as the "Black Spring".

On July 31, 2006 Fidel Castro temporarily delegated his major duties to his brother, First Vice President, Raúl Castro, while Fidel recovered from surgery for an "acute intestinal crisis with sustained bleeding".[citation needed] On 2 December 2006, Fidel was too ill to attend the 50th anniversary commemoration of the Granma boat landing, fuelling speculation that he had stomach cancer,[64] although there was evidence his illness was a digestive problem and not terminal.

In January 2008, footage was released of Fidel meeting Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, in which Castro "appeared frail but stronger than three months ago". In February 2008 Fidel announced his resignation as President of Cuba, and on 24 February Raúl was elected as the new President. In his acceptance speech, Raúl promised that some of the restrictions that limit Cubans' daily lives would be removed. In March 2009, Raúl Castro purged some of Fidel's officials.

Cuba is an archipelago of islands located in the northern Caribbean Sea at the confluence with the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. The United States lies to the north-west, the Bahamas to the north, Haiti to the east, Jamaica and the Cayman Islands to the south, and Mexico to the west. Cuba is the principal island, surrounded by four smaller groups of islands: the Colorados Archipelago on the northwestern coast, the Sabana-Camagüey Archipelago on the north-central Atlantic coast, the Jardines de la Reina on the south-central coast and the Canarreos Archipelago on the southwestern coast. The main island is 766 km (476 mi) long, constituting most of the nation's land area (105,006 km2 (40,543 sq mi)) and is the sixteenth-largest island in the world by land area. The main island consists mostly of flat to rolling plains apart from the Sierra Maestra mountains in the southeast, whose highest point is Pico Turquino (1,975 m (6,480 ft)). The second largest island is Isla de la Juventud (Isle of Youth) in the Canarreos archipelago, with an area of 3,056 km2 (1,180 sq mi). Cuba has a total land area of 110,860 km2 (42,803 sq mi).

The local climate is tropical, though moderated by northeasterly trade winds that blow year-round. In general , there is a drier season from November to April, and a rainier season from May to October. The average temperature is 21 °C (70 °F) in January and 27 °C (81 °F) in July. The warm temperatures of the Caribbean Sea and the fact that Cuba sits across the entrance to the Gulf of Mexico combine to make the country prone to frequent hurricanes. These are most common in September and October.

The most important mineral resource is nickel, of which Cuba has the world's second largest reserves after Russia. A Canadian energy company operates a large nickel mining facility in Moa. Cuba is also the world's fifth largest producer of refined cobalt, a byproduct of nickel mining operations.[91] Recent oil exploration has revealed that the North Cuba Basin could produce approximately 4.6 billion barrels (730,000,000 m3) to 9.3 billion barrels (1.48×109 m3) of oil. In 2006, Cuba started to test-drill these locations for possible exploitation.

Prior to the arrival of the Spanish, the island was inhabited by Native American peoples known as the Taíno and Ciboney whose ancestors migrated from the mainland of North, Central and South America several centuries earlier. The Taíno were farmers and the Ciboney were farmers and hunter-gatherers; some have suggested that copper trade was significant and mainland artifacts have been found.

On October 12, 1492, Christopher Columbus landed near what is now Baracoa, claimed the island for the new Kingdom of Spain, and named Isla Juana after Juan, Prince of Asturias. In 1511 the first Spanish settlement was founded by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar at Baracoa; other towns soon followed including the future capital, San Cristobal de la Habana founded in 1515. The Spanish enslaved the approximately 100,000 indigenous people who resisted conversion to Christianity, setting them primarily to the task of searching for gold, and within a century European infectious diseases had virtually wiped out the indigenous people.

Cuba remained a Spanish possession for almost 400 years (1511–1898), with an economy based on plantations agriculture, mining and the export of sugar, coffee and tobacco to Europe and later to North America. The work was done primarily by African slaves brought to the island when the British owned it in 1762. The small land-owning elite of Spanish settlers held social and economic power, supported by a population of Spaniards born on the island , other Europeans, and African-descended slaves. In the 1820s, when the rest of Spain's empire in Latin America rebelled and formed independent states, Cuba remained loyal, although there was some agitation for independence, leading the Spanish Crown to give it the motto "La Siempre Fidelísima Isla" . This loyalty was due partly to Cuban settlers' dependence on Spain for trade, protection from pirates, protection against a slave rebellion and partly because they feared the rising power of the United States more than they disliked Spanish rule.

Independence from Spain was the motive for a rebellion in 1868 led by Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, resulting in a prolonged conflict known as the Ten Years' War. The U.S. declined to recognize the new Cuban government, though many European and Latin American nations had done so. In 1878 the Pact of Zanjón ended the conflict, with Spain promising greater autonomy to Cuba. In 1879–1880, Cuban patriot Calixto Garcia attempted to start another war, known as the Little War, but received little support. Slavery was abolished in 1886, although the African-descended minority remained socially and economically oppressed. During this period, rural poverty in Spain provoked by the Spanish Revolution of 1868 and its aftermath led to increased Spanish emigration to Cuba. During the 1890s pro-independence agitation was revived in part by resentment of the restrictions imposed on Cuban trade by Spain and hostility to Spain's increasingly oppressive and incompetent administration of Cuba. Few of Spain's promises for economic reform in the Pact of Zanjón were kept.

In 1892, an exiled dissident, José Martí, founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party in New York, with the aim of achieving Cuban independence. In January 1895, Martí travelled to Montecristi, Santo Domingo to join the efforts of Máximo Gómez. Martí wrote down his political views in the Manifesto of Montecristi. Fighting against the Spanish army began in Cuba on 24 February 1895, but Marti was unable to reach Cuba until 11 April 1895. Marti was killed on 19 May 1895, in the battle of Dos Rios. His death immortalized him and he has become Cuba's national hero. Around 200,000 Spanish troops outnumbered the much smaller rebel army which relied mostly on guerrilla and sabotage tactics. The Spaniards began a campaign of suppression. General Valeriano Weyler, military governor of Cuba, herded the rural population into what he called reconcentrados, described by international observers as "fortified towns". These are often considered the prototype for 20th century concentration camps. Between 200,000 and 400,000 Cuban civilians died from starvation and disease in the camps, numbers verified by the Red Cross and U.S. Senator Redfield Proctor. U.S. and European protests against Spanish conduct on the island followed.

The U.S. battleship Maine arrived in Havana on 25 January 1898 to offer protection to the 8,000 American residents on the island; but the Spanish saw this as intimidation. On the evening of 15 February 1898, the Maine blew up in the harbor, killing 252 crew that night; another 8 died of their wounds in hospital over the next few days. A Naval Board of Inquiry, headed by Captain William Sampson, was appointed to investigate the cause of the explosion on the Maine. Having examined the wreck and taken testimony from eyewitnesses and experts, the board reported on 21 March 1898, that the Maine had been destroyed by "a double magazine set off from the exterior of the ship, which could only have been produced by a mine". The facts remain disputed today, although an investigation by Admiral Hyman G. Rickover in 1976 established that the blast was most likely a large internal explosion, caused by spontaneous combustion in inadequately ventilated bituminous coal which ignited gunpowder in an adjacent magazine. The board was unable to fix the responsibility for the disaster, but a furious American populace, fueled by an active press—notably the newspapers of William Randolph Hearst—concluded that the Spanish were to blame amd demanded action. The U.S. Congress passed a resolution calling for intervention and President William McKinley complied. Spain and the United States declared war on each other in late April.

After the Spanish-American War, Spain and the United States signed the Treaty of Paris (1898), by which Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam were ceded to the U.S. for the sum of $20 million. Under the same treaty Spain relinquished all claim of sovereignty over the title to Cuba. Theodore Roosevelt, who had fought in the Spanish-American War and had some sympathies with the independence movement, succeeded McKinley as U.S. President in 1901 and abandoned the 20-year treaty proposal. Instead, Cuba gained formal independence from the United States on May 20, 1902 as the Republic of Cuba. Under the new constitution, however, the U.S. retained the right to intervene in Cuban affairs and to supervise its finances and foreign relations. Under the Platt Amendment, the U.S. leased the Guantánamo Bay naval base from Cuba.

In 1906, following disputed elections, the first president, Tomás Estrada Palma, faced an armed revolt by independence war veterans who defeated the meager government forces. The U.S. intervened by occupying Cuba and named Charles Edward Magoon as Governor for three years. For many years afterwards, Cuban historians attributed Magoon's governorship as having introduced political and social corruption. In 1908 self-government was restored when José Miguel Gómez was elected President, but the U.S. continued intervening in Cuban affairs. In 1912 the Partido Independiente de Color attempted to establish a separate black republic in Oriente Province, but were suppressed by General Monteagudo with considerable bloodshed.

During World War I, Cuba shipped considerable quantities of sugar to Britain, avoiding U-boat attack, by the subterfuge of shipping sugar to Sweden. The Menocal government declared war on Germany very soon after the U.S. did.

Despite frequent outbreaks of disorder, constitutional government was maintained until 1930, when Gerardo Machado y Morales suspended the constitution. During Machado's tenure, a nationalistic economic program was pursued with several major national development projects undertaken, including Carretera Central and El Capitolio. Machado's hold on power was weakened following a decline in demand for exported agricultural produce due to the Great Depression, and to attacks first by independence war veterans, and later by covert terrorist organizations, principally the ABC.

During a general strike in which the Communist Party took the side of Machado the senior elements of the Cuban army forced Machado into exile and installed Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y Quesada, son of Cuba's founding father , as President. During September 4–5, 1933 a second coup overthrew Céspedes, leading to the formation of the first Ramón Grau government. Notable events in this violent period include the separate sieges of Hotel Nacional de Cuba and Atares Castle. This government lasted 100 days but engineered radical socialistic changes in Cuban society and a rejection of the Platt amendment. In 1934 Fulgencio Batista and the army replaced Grau with Carlos Mendieta.

Batista was finally elected as President democratically in the elections of 1940,[ and his administration carried out major social reforms. Several members of the Communist Party held office under his administration. Batista's administration formally took Cuba to the Allies of World War II camp in the World War II, declaring war on Japan on December 9, 1941, then on Germany and Italy on December 11, 1941. Cuba was not greatly involved in combat during World War II.

Ramón Grau won the 1944 elections. Carlos Prío Socarrás won the 1948 elections. The influx of investment fueled a boom which did much to raise living standards across the board and create a prosperous middle class in most urban areas, although the gap between rich and poor became wider and more obvious.

The 1952 election was a three-way race. Roberto Agramonte of the Ortodoxos party led in all the polls, followed by Dr Aurelio Hevia of the Auténtico party, and running a distant third was Batista, seeking a return to office. Both Agramonte and Hevia had decided to name Col. Ramón Barquín to head the Cuban armed forces after the elections. Barquín, then a diplomat in Washington, DC, was a top officer who commanded the respect of the professional army and had promised to eliminate corruption in the ranks. Batista feared that Barquín would oust him and his followers, and when it became apparent that Batista had little chance of winning, he staged a coup on March 10, 1952 and held power with the backing of a nationalist section of the army as a "provisional president" for the next two years. Justo Carrillo told Barquín in Washington in March 1952 that the inner circles knew that Batista had aimed the coup at him; they immediately began to conspire to oust Batista and restore democracy and civilian government in what was later dubbed La Conspiracion de los Puros de 1956 . In 1954 Batista agreed to elections. The Partido Auténtico put forward ex-President Grau as their candidate, but he withdrew amid allegations that Batista was rigging the elections in advance.

In April 1956 Batista had given the orders for Barquín to become General and chief of the army. But Barquin decided to move forward with his coup and secure total power. On April 4, 1956 a coup by hundreds of career officers led by Col. Barquín was frustrated by Rios Morejon. The coup broke the backbone of the Cuban armed forces. The officers were sentenced to the maximum terms allowed by Cuban Martial Law. Barquín was sentenced to solitary confinement for eight years. La Conspiración de los Puros resulted in the imprisonment of the commanders of the armed forces and the closing of the military academies.

Cuba had Latin America's highest per capita consumption rates of meat, vegetables, cereals, automobiles, telephones and radios. In 1958, Cuba was a relatively well-advanced country, certainly by Latin American standards, and in some cases by world standards.Cuban's workers enjoyed some of the highest wages in the world. Cuba attracted more immigrants, primarily from Europe, as a percentage of population than the US. The United Nations noted Cuba for its large middle class. On the other hand, Cuba was affected by perhaps the largest labor union privileges in Latin America, including bans on dismissals and mechanization. They were obtained in large measure "at the cost of the unemployed and the peasants", leading to disparities. Between 1933 and 1958, Cuba extended economic regulations enormously, causing economic problems. Unemployment became relatively large; graduates entering the workforce could not find jobs. The middle class, which compared Cuba to the United States, became increasingly dissatisfied with the unemployment, while labor unions supported Batista until the very end.

The United States government imposed an arms embargo on the Cuban government on March 14, 1958. On December 2, 1956 a party of 82 people, led by Fidel Castro, had landed with the intention of establishing an armed resistance movement in the Sierra Maestra. By late 1958 they had broken out of the Sierra Maestra and launched a general insurrection, joined by various people. When the group captured Santa Clara, Batista fled the country to exile in Portugal. Barquín negotiated the symbolic change of command between Camilo Cienfuegos, Che Guevara, Raul Castro and his brother Fidel Castro, after the Supreme Court decided that the Revolution was the source of law and its representative should assume command. Castro's forces entered the capital on January 8, 1959. Shortly afterwards, a liberal lawyer, Dr Manuel Urrutia Lleó became president; he was backed by Castro's 26th of July Movement, because they believed his appointment would be welcomed by the United States. Disagreements within the government culminated in Urrutia's resignation in July 1959; he was replaced by Osvaldo Dorticós, who served as president until 1976. Castro became prime minister in February 1959, succeeding José Miró in that post.

Fidel Castro became prime minister of Cuba in February 1959. In its first year, the new revolutionary government expropriated private property with little or no compensation, nationalised public utilities, tightened controls on the private sector and closed down the mafia-controlled gambling industry. The CIA conspired with the Chicago mafia in 1960 and 1961 to assassinate Fidel Castro, according to documents declassified in 2007.

Some of these measures were undertaken by Fidel Castro's government in the name of the program outlined in the Manifesto of the Sierra Maestra, while in the Sierra Maestra. The government nationalized private property totaling about $25 billion US dollars, out of which American property made up only over US $1.0 billions.

By the end of 1960, all opposition newspapers had been closed down, and all radio and television stations were in state control. Moderates, teachers and professors were purged. In any year, about 20,000 dissenters were held and tortured under inhuman prison conditions.Groups such as homosexuals were locked up in internment camps in the 1960s, where they were subject to medical-political "re-education". One estimate is that 15,000 to 17,000 people were executed. The Communist Party strengthened its one-party rule, with Castro as supreme leader. Fidel's brother, Raul Castro, became the army chief. Loyalty to Castro became the primary criteria for all appointments. In September 1960, the regime created a system known as Committees for the Defense of the Revolution , which provided neighborhood spying. In the 1961 New Year's Day parade, the administration exhibited Soviet tanks and other weapons.Eventually, the tiny island nation built up the second largest armed forces in Latin America, second only to Brazil. Cuba became a privileged client-state of the Soviet Union.

By 1961, hundreds of thousands of Cubans had left for the United States. The 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion was an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow the Cuban government by a U.S.-trained force of Cuban exiles with U.S. military support. The plan was launched in April 1961, less than three months after John F. Kennedy became the U.S. President. The Cuban armed forces, trained and equipped by Eastern Bloc nations, defeated the exiles in three days. The bad Cuban-American relations were exacerbated the following year by the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the Kennedy administration demanded the immediate withdrawal of Soviet missiles placed in Cuba, which was a response to U.S. nuclear missiles in Turkey and the Middle East. The Soviets and Americans soon agreed on the removal of Soviet missiles from Cuba and American missiles secretly from Turkey and the Middle East within a few months. Kennedy also agreed not to invade Cuba in the future. Cuban exiles captured during the Bay of Pigs Invasion were exchanged for a shipment of supplies from America.[34] By 1963, Cuba was moving towards a full-fledged Communist system modeled on the USSR. The U.S. imposed a complete diplomatic and commercial embargo on Cuba and began Operation Mongoose.

In 1965, Castro merged his revolutionary organizations with the Communist Party, of which he became First Secretary, and Blas Roca became Second Secretary. Roca was succeeded by Raúl Castro, who, as Defense Minister and Fidel's closest confidant, became and has remained the second most powerful figure in Cuba. Raúl's position was strengthened by the departure of Che Guevara to launch unsuccessful insurrectionss in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and then Bolivia, where he was killed in 1967.

During the 1970s, Castro dispatched tens of thousands troops in support of Soviet-supported wars in Africa, particularly the MPLA in Angola and Mengistu Haile Mariam in Ethiopia. The standard of living in 1970s was "extremely spartan" and discontent was rife. Fidel Castro admitted the failures of economic policies in a 1970 speech. By the mid-1970s, Castro started economic reforms.

Cuba was expelled from the Organization of American States in 1962 in support of the U.S. embargo, but in 1975 the OAS lifted all sanctions against Cuba and both Mexico and Canada broke ranks with the US by developing closer relations with Cuba. On 3 June 2009 the OAS adopted a contentious resolution to end the 47-year exclusion of Cuba, but the U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton walked out in protest as the resolution was being drafted. Cuban leaders have repeatedly announced they are not interested in rejoining the OAS.

As of 2002, some 1.2 million persons of Cuban background (about 10% of the current population of Cuba) reside in the U.S., Many of them left the island for the U.S., often by sea in small boats and fragile rafts. On 6 April 1980, 10,000 Cubans stormed the Peruvian embassy in Havana seeking political asylum. The following day, the Cuban government granted permission for the emigration of Cubans seeking refuge in the Peruvian embassy. On 16 April, 500 Cubans left the Peruvian Embassy for Costa Rica. On 21 April, many of those Cubans started arriving in Miami via private boats and were halted by the U.S. State Department, but the emigration continued, because Castro allowed anyone who desired to leave the country to do so through the port of Mariel. Over 125,000 Cubans emigrated to the U.S. before the flow of vessels ended on 15 June.

Castro's rule was severely tested in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse . The food shortages were similar to North Korea; priority was given to the elite classes and the military, while ordinary people had little to eat. The regime did not accept American donations of food, medicines and cash until 1993. On 5 August 1994, state security dispersed protesters in a spontaneous popular uprising in Havana.

Cuba has found a new source of aid and support in the People's Republic of China, and new allies in Hugo Chávez, President of Venezuela and Evo Morales, President of Bolivia, both major oil and gas exporters. In 2003, the regime arrested and imprisoned a large number of civil activists, a period known as the "Black Spring".

On July 31, 2006 Fidel Castro temporarily delegated his major duties to his brother, First Vice President, Raúl Castro, while Fidel recovered from surgery for an "acute intestinal crisis with sustained bleeding".[citation needed] On 2 December 2006, Fidel was too ill to attend the 50th anniversary commemoration of the Granma boat landing, fuelling speculation that he had stomach cancer,[64] although there was evidence his illness was a digestive problem and not terminal.

In January 2008, footage was released of Fidel meeting Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, in which Castro "appeared frail but stronger than three months ago". In February 2008 Fidel announced his resignation as President of Cuba, and on 24 February Raúl was elected as the new President. In his acceptance speech, Raúl promised that some of the restrictions that limit Cubans' daily lives would be removed. In March 2009, Raúl Castro purged some of Fidel's officials.

Kingston

Kingston is the capital and largest city of Jamaica and is located on the southeastern coast of the island country. It faces a natural harbour protected by the Palisadoes, a long sand spit which connects Port Royal and the Norman Manley International Airport to the rest of the island. In the Americas, Kingston is the largest predominantly English-speaking city south of the United States.